Mosaics in the Museum

Original Beth Shean Gallery, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

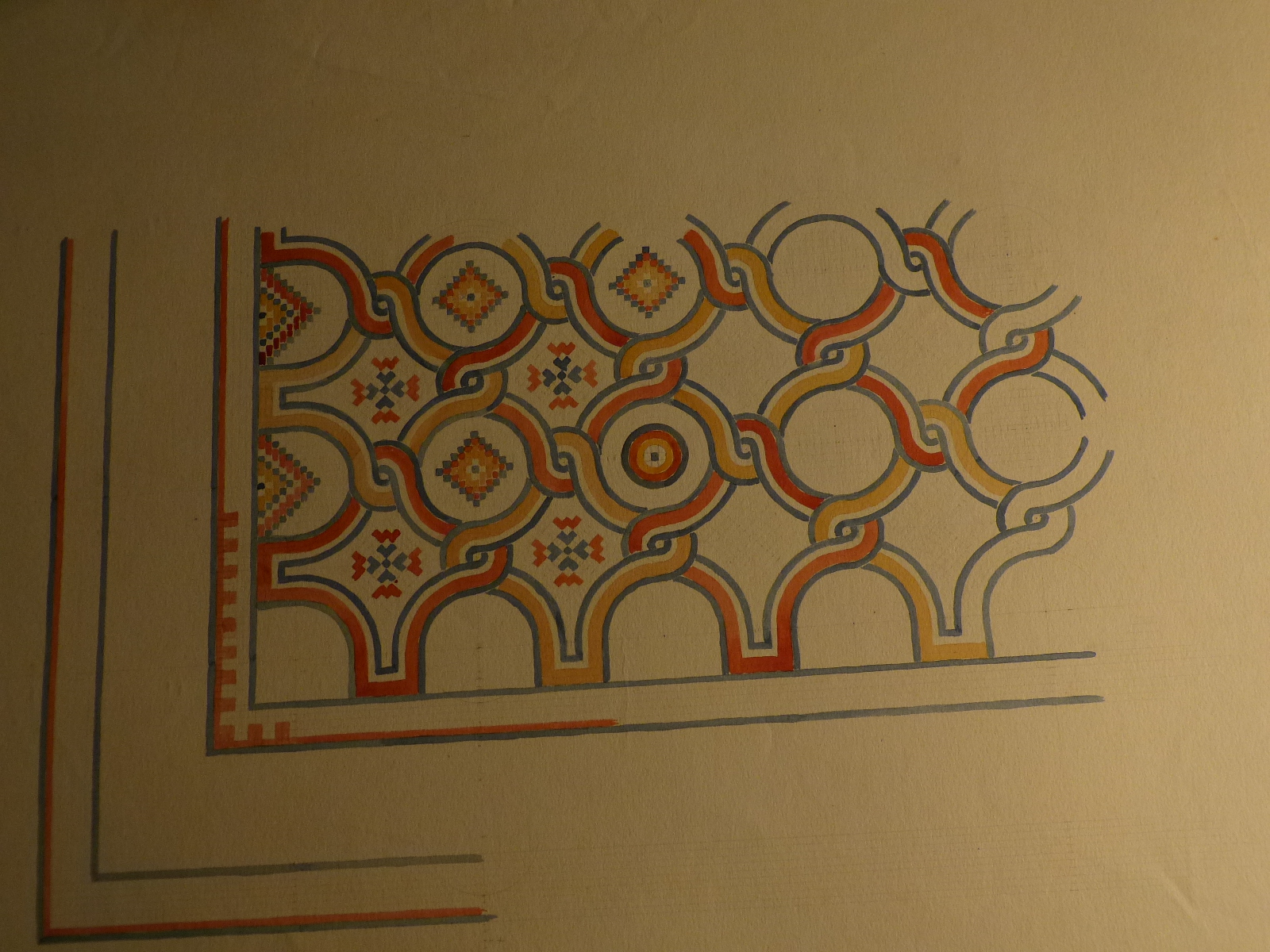

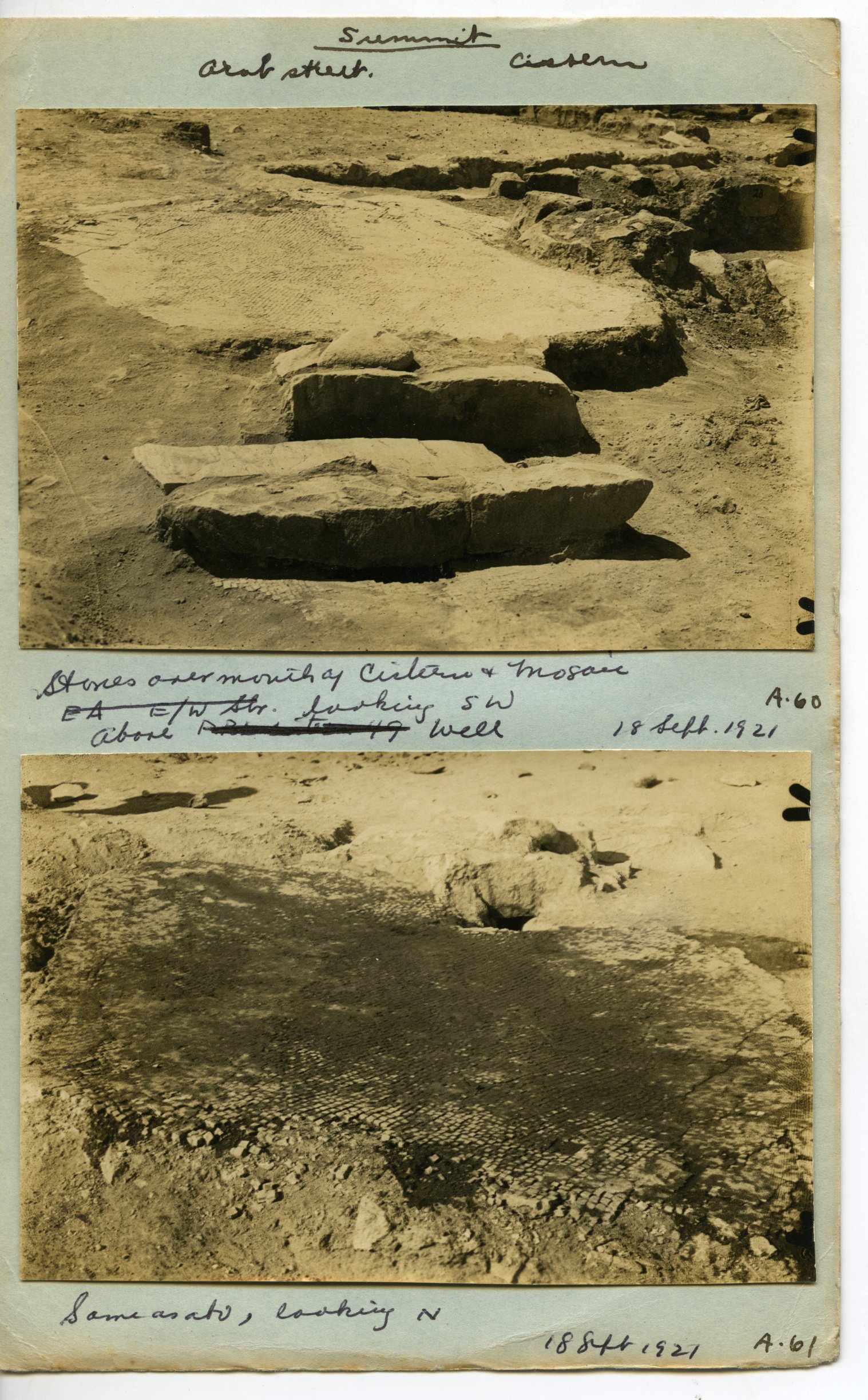

While the mosaics discussed as part of this digital exhibit are not currently on view in the Penn Museum, several panels were once prominently displayed in the gallery of the Penn Museum now housing part of the Egyptian collection. At the end of the 1921 excavation season, director Clarence Fisher described the process for removing the panels from the site and shipping them to the University: “The large pieces of mosaic floors have been safely removed from the works and are now being reinforced with strips of laths laid in plaster. A quantity of wood has arrived for making boxes and a local carpenter will be engaged to make fine heavy cases for the mosaics and such of the objects as need special packing” (Field Diary entry, October 17, 1921). At some point following their arrival, several panels were “completed” or filled in with additional modern tesserae, with restorers taking care to delineate their own creations from those of the Byzantine mosaicists.

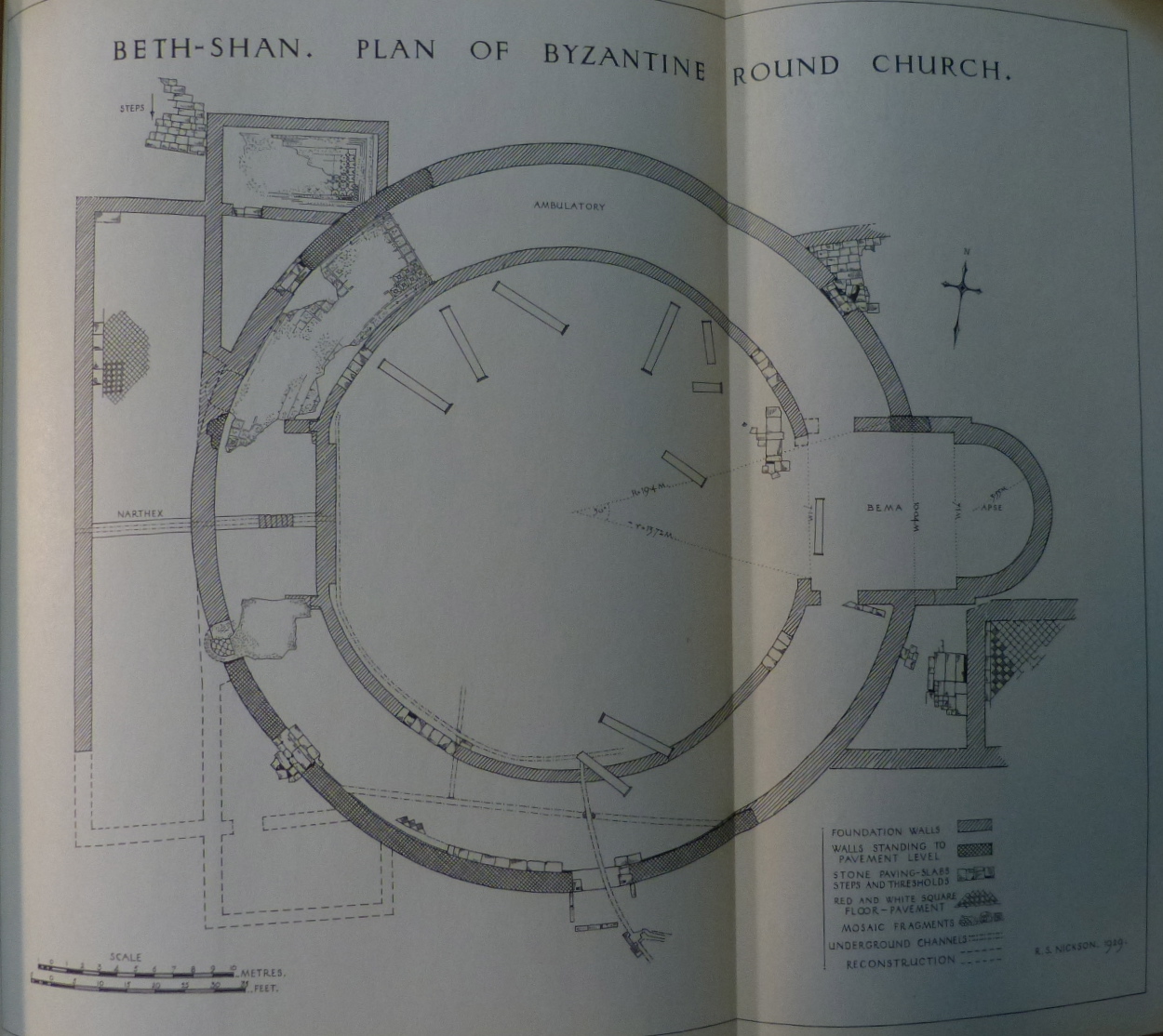

Attempting to re-create a Byzantine visual experience in the museum is challenged by their decontextualization through removal from site, structure, and surrounding floor mosaics. However, archaeologists working with stratified sites like Beth Shean that have been occupied for millennia must grapple with the choice between removing objects and structures to continue delving into the layers of history or preservation at a particular chronological period. In removing much of the Byzantine material from the site, Fisher was able to reach levels of settlement on the Tel dating back to the Early Bronze Age. Fortunately, the careful and thorough documentation of artifacts and structures in their original context prior to their removal has allowed modern scholars to continue to work with the pieces as an assemblage that allows for a deeper understanding of social, cultural, and economic life of the post-Antique settlement.

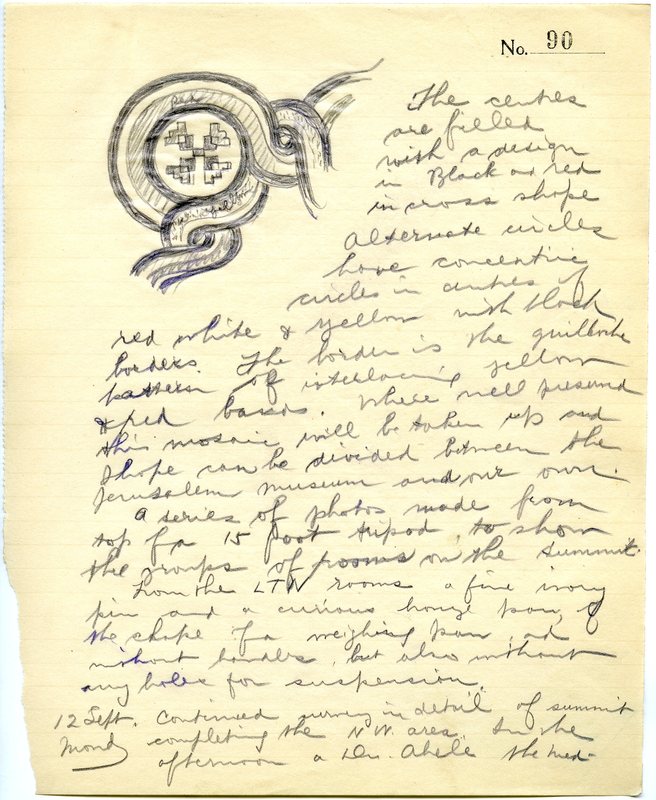

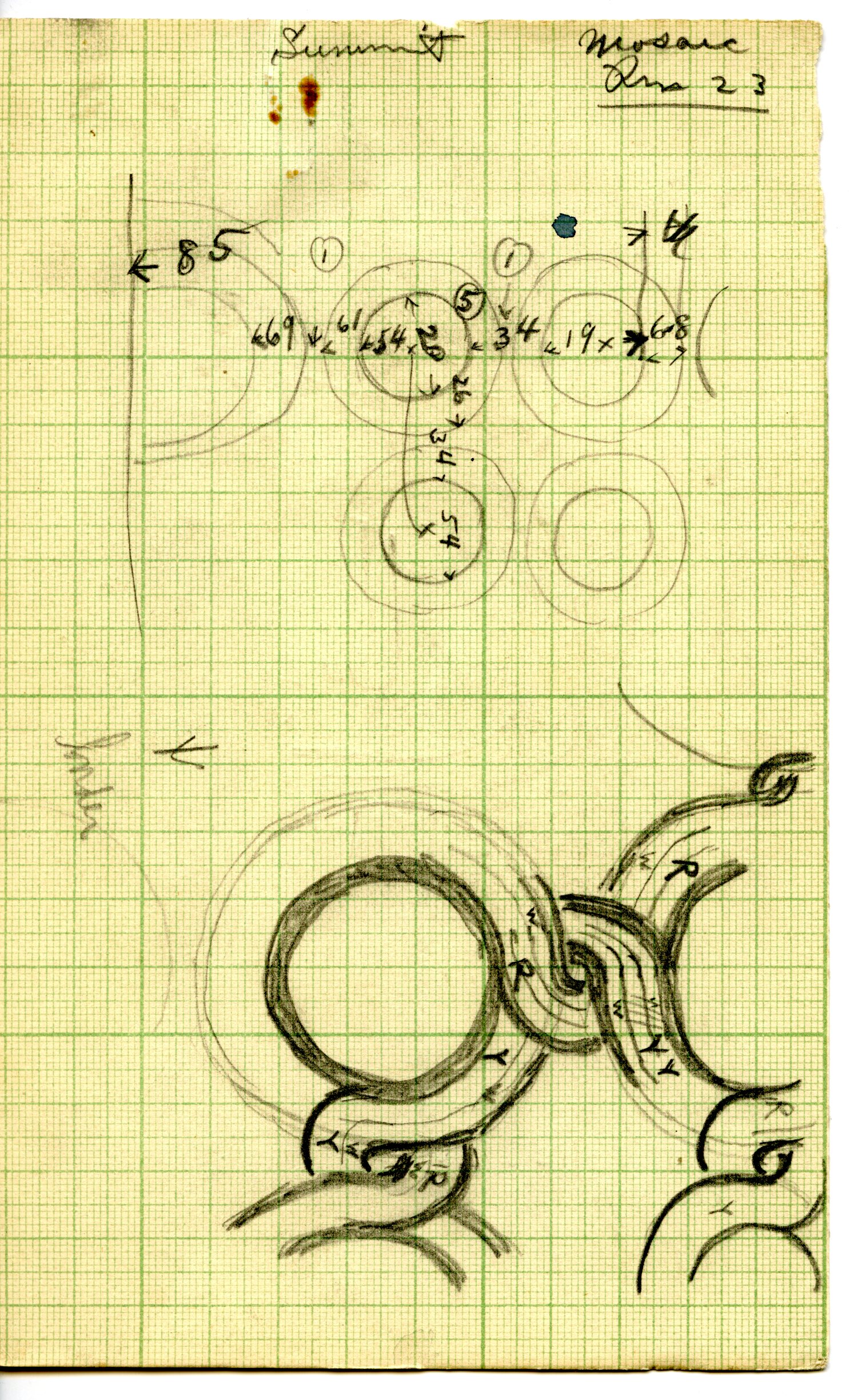

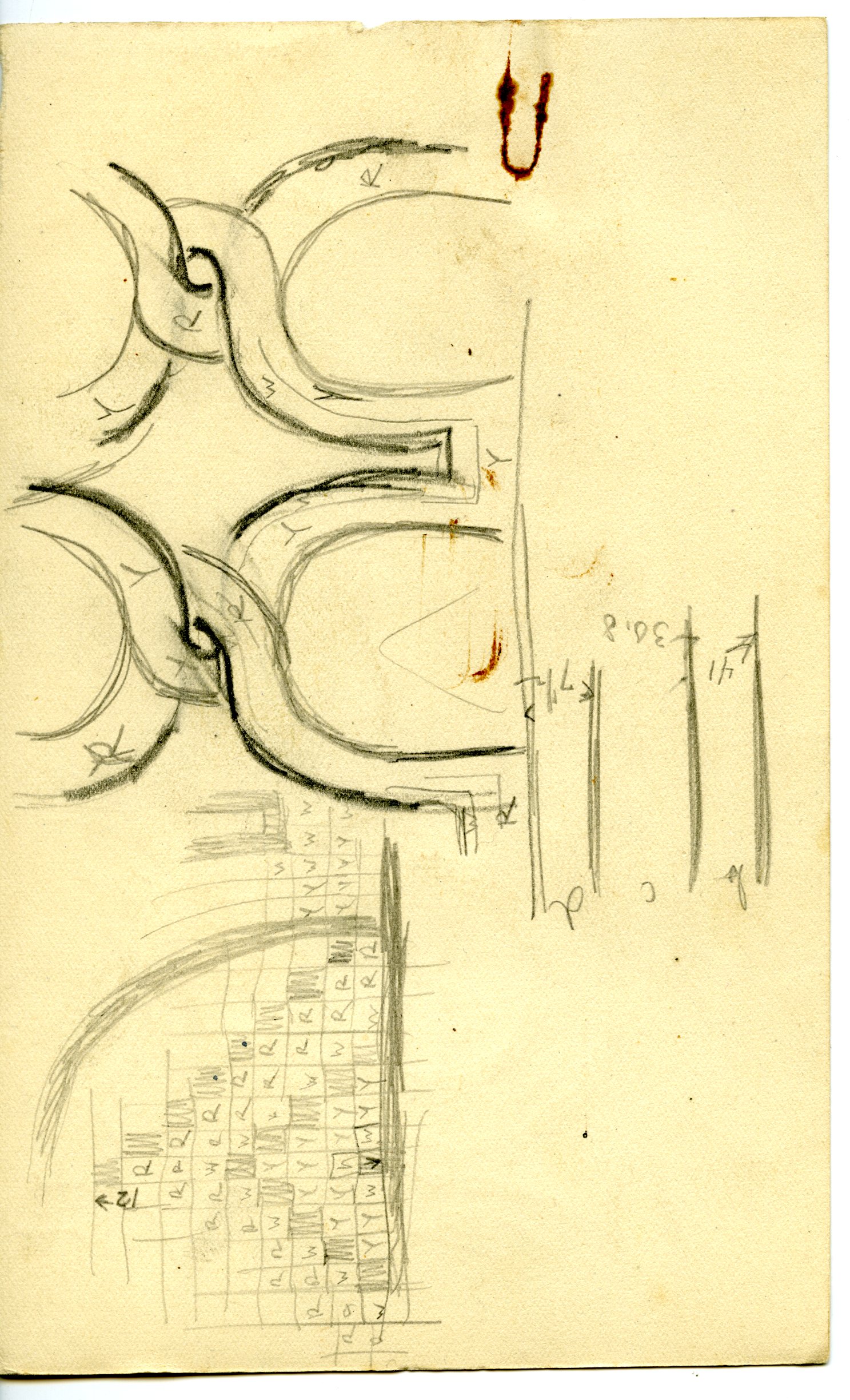

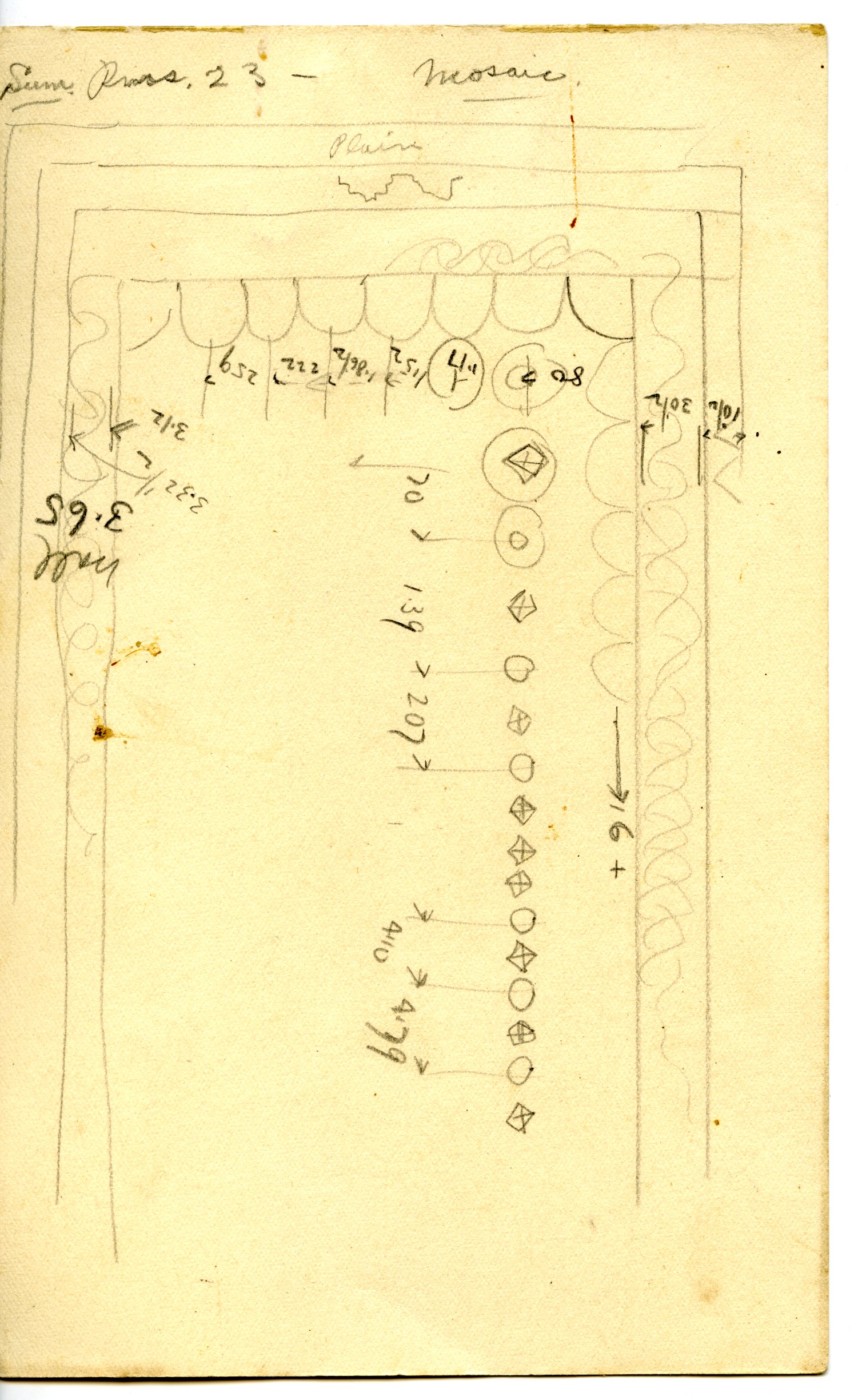

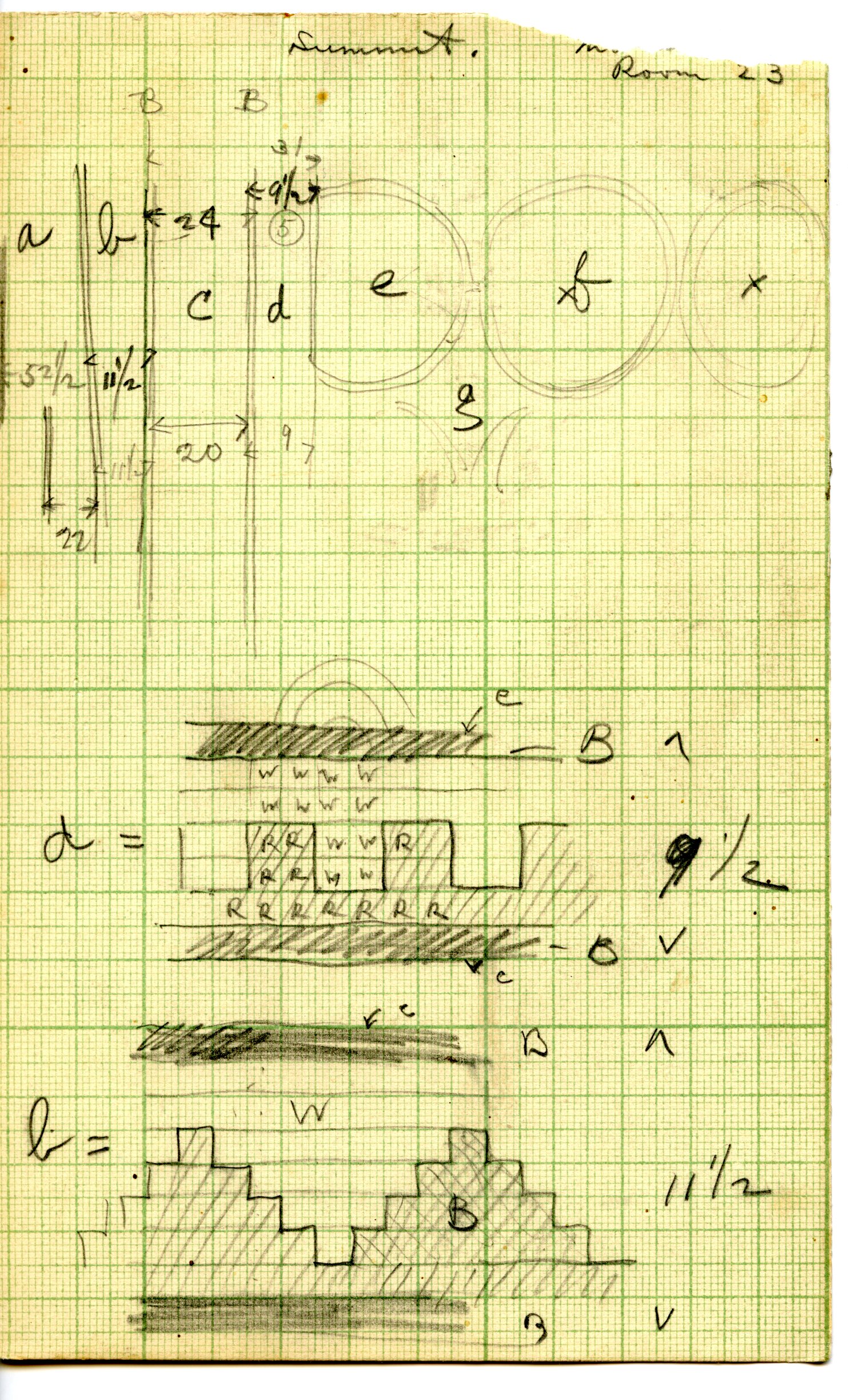

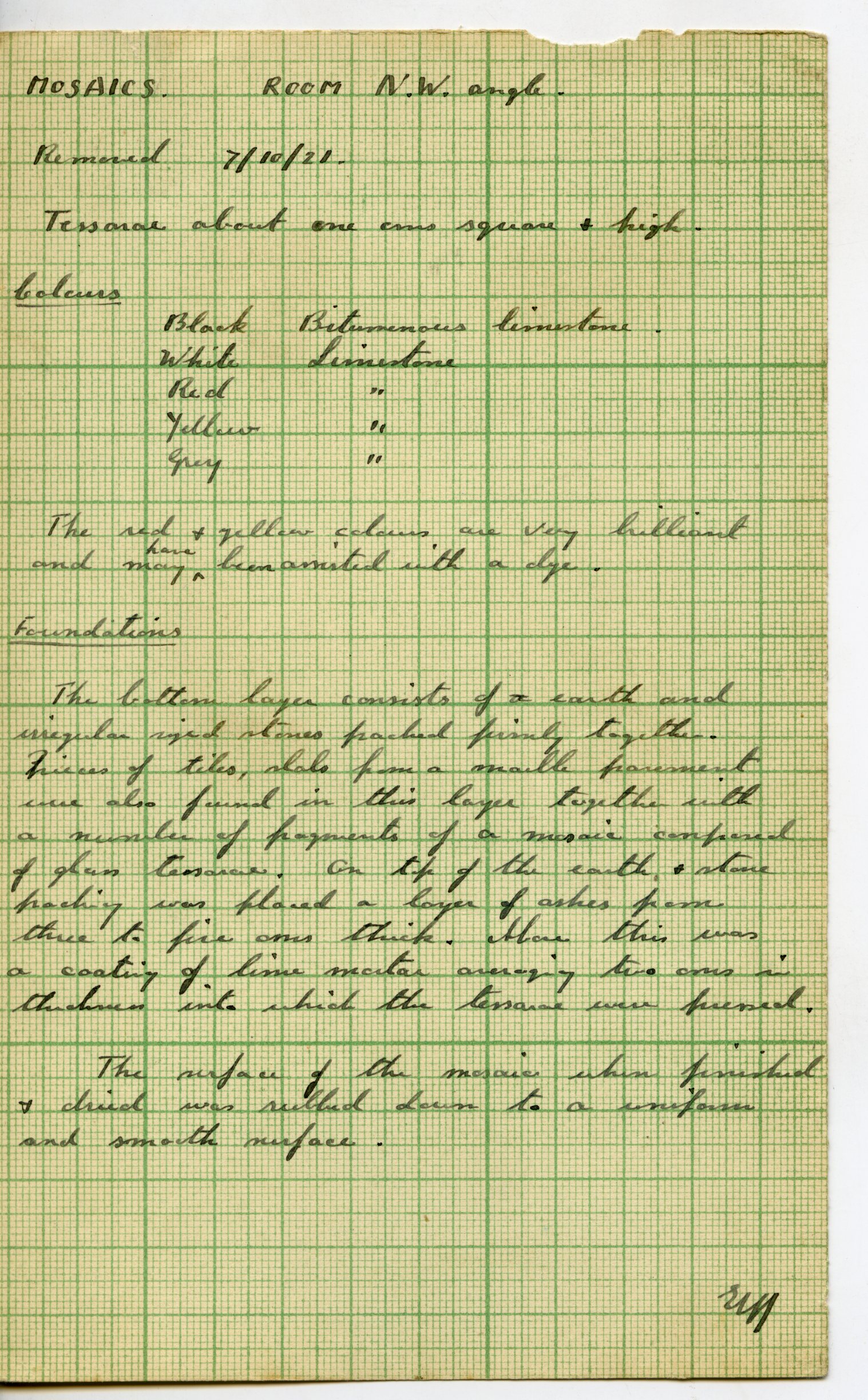

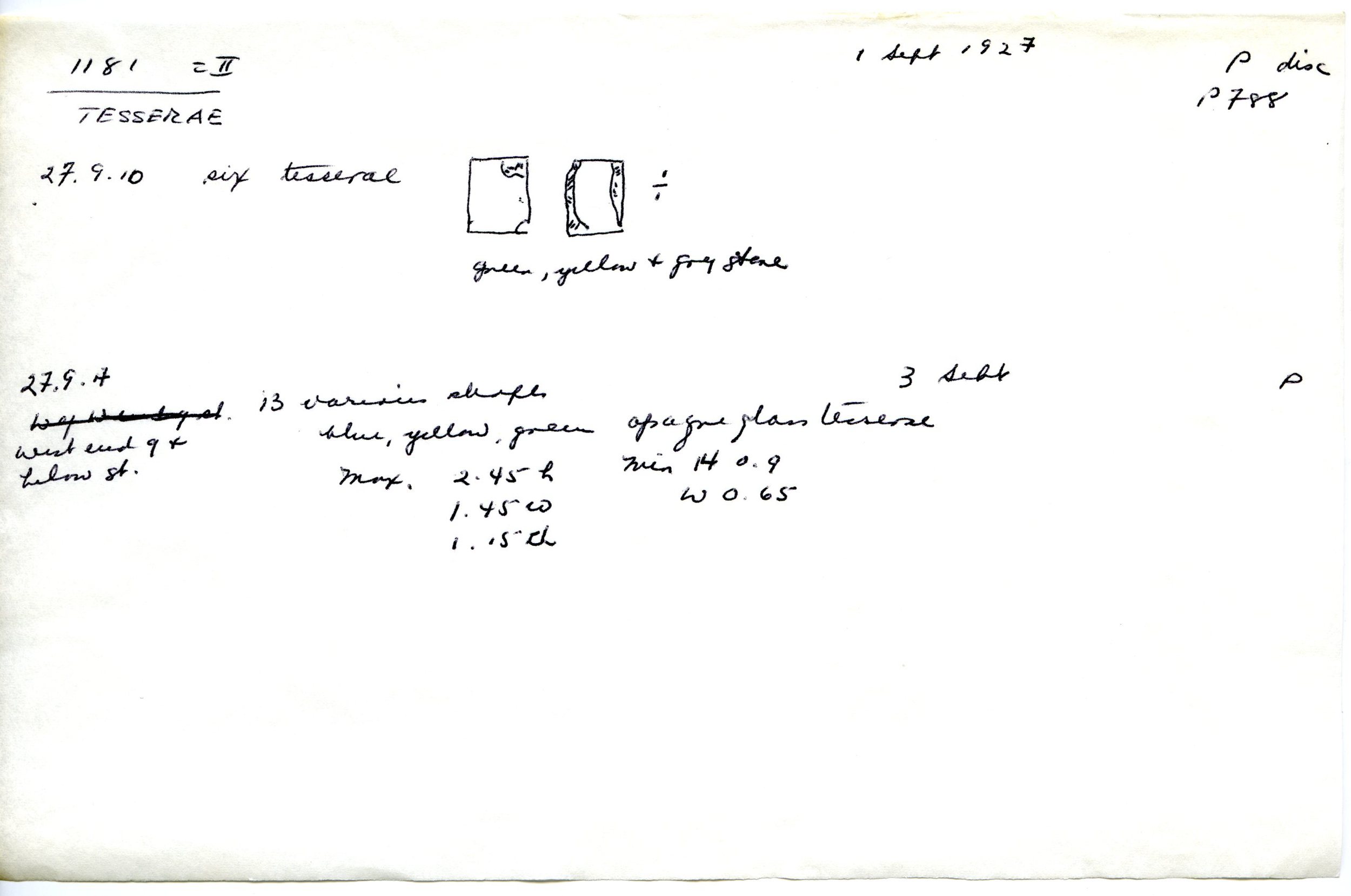

The Penn Museum Archives play a large role in this process of contextual reconstruction and interpretation, with over 85,000 documents related to the excavation. Fisher and his team kept detailed records of their day-to-day excavation work, and often sketched pieces and attempted to visually understand them as they were uncovered. Plans of structures and levels of the settlement allow us to reunite the mosaic floor panels with the walls and objects that surrounded them at the moment of their burial, and photographs of the works in situ allow us to reconstruct the relationship between the Penn Museum panels and their surroundings.

Selection of Mosaic-Related Documents, Penn Museum Archives