Excavating Domestic Space

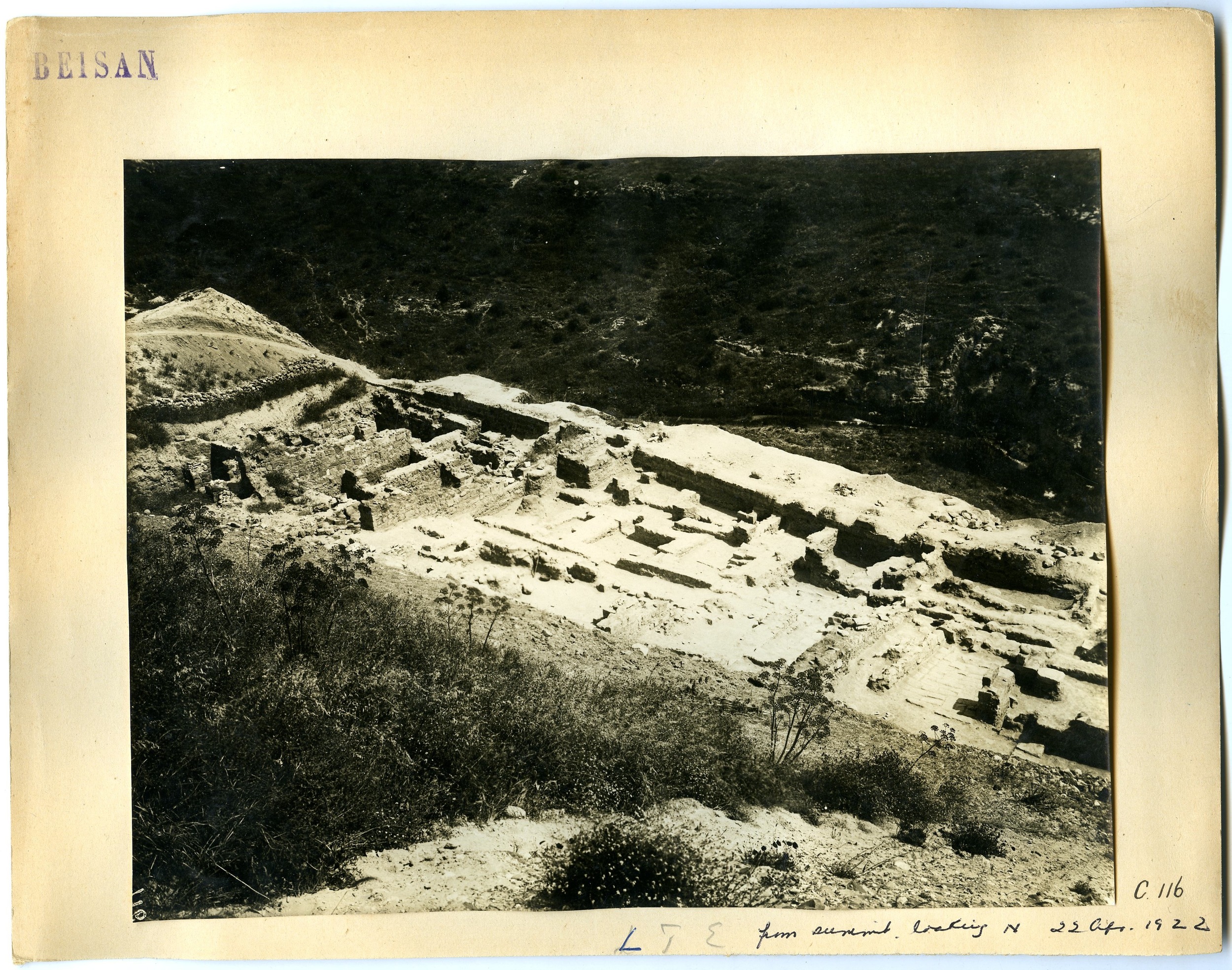

Unlike several of the other galleries in this exhibition, defining domestic space cannot be done in quite the same way as defining objects by material type. To define "domestic space" requires the crossing of categories, and the pulling together of all sorts of evidence from all sorts of places - especially since as of yet (April 2014) no complete urban Byzantine dwelling has been discovered. Many of the finds in these "domestic" spaces reflect the lives of individuals, and so often tend not to be as flashy or pretty as other types of collections. Despite this, these simple objects (spoons, pots, lamps, grindstones, bric-a-brac) often speak to the behaviour and lives of individuals in a way few objects can. As such, they provide another way for us to model the past.

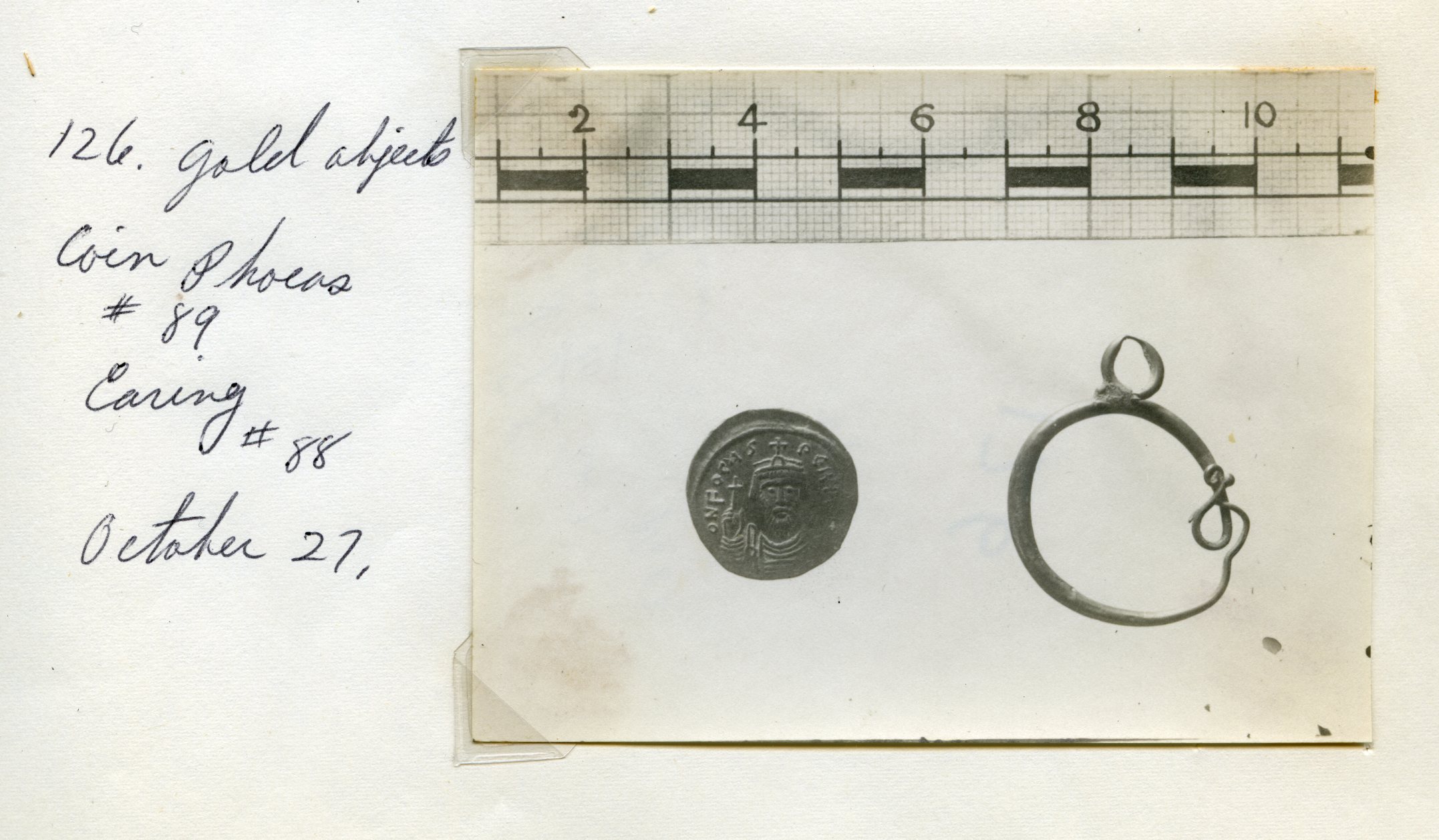

Apart from the large round church which is clearly identifiable on the ground plans, the other Byzantine remains (namely, the domestic space) are very fragmented. As with most other urban sites, it remains impossible to reconstruct what a single dwelling would have looked like. From a fortunately discovered coin of Phocas, however, we can infer that wealthy Byzantines used this space during or shortly after the years 602-610 (the duration of the reign of Phocas).

Coin of Emperor Phocas (602-610) found in House III on the tell. Photographed in 1921, alongside a gold earring now found in the University of Pennsylvania collection. The coin is kept at the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem.

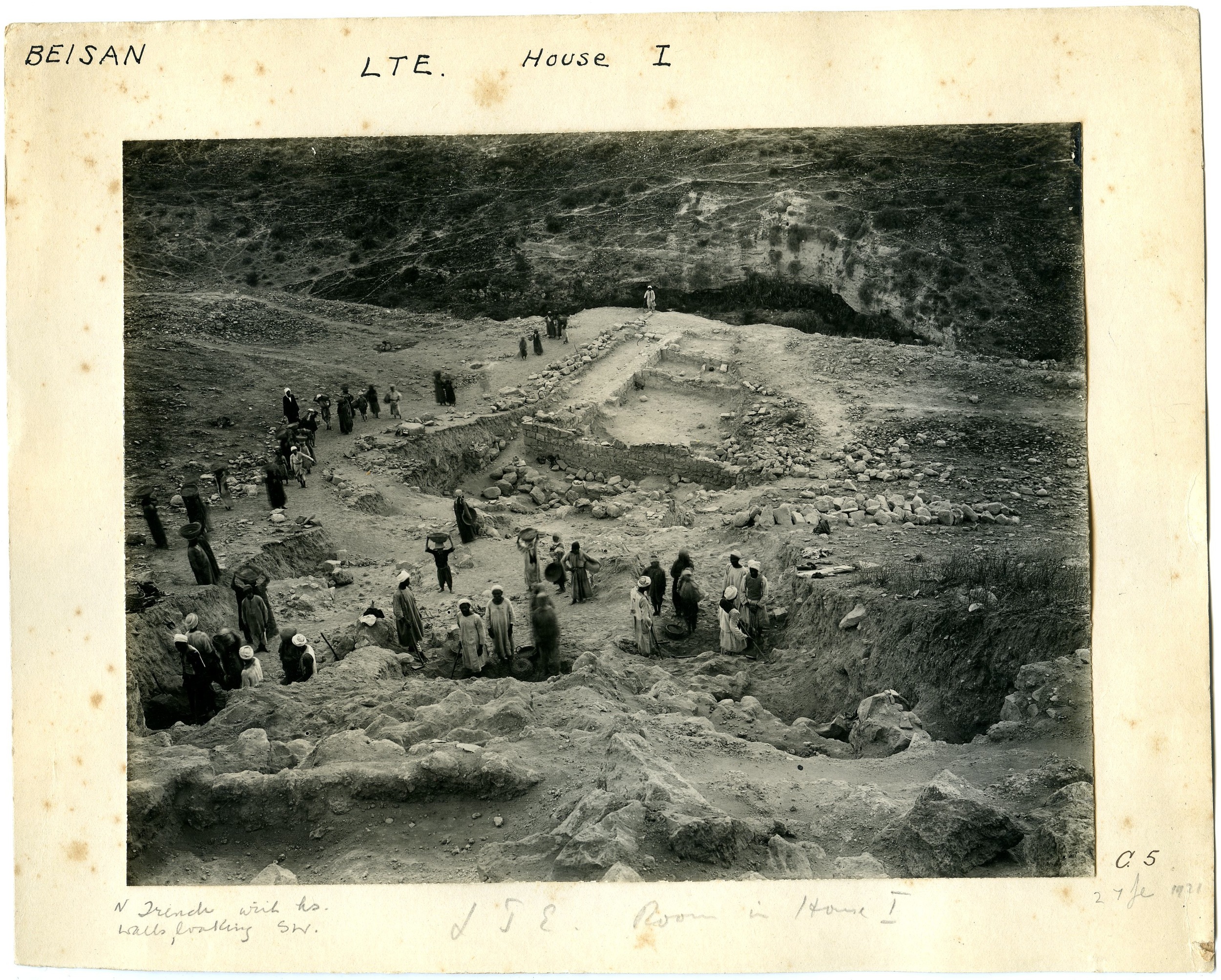

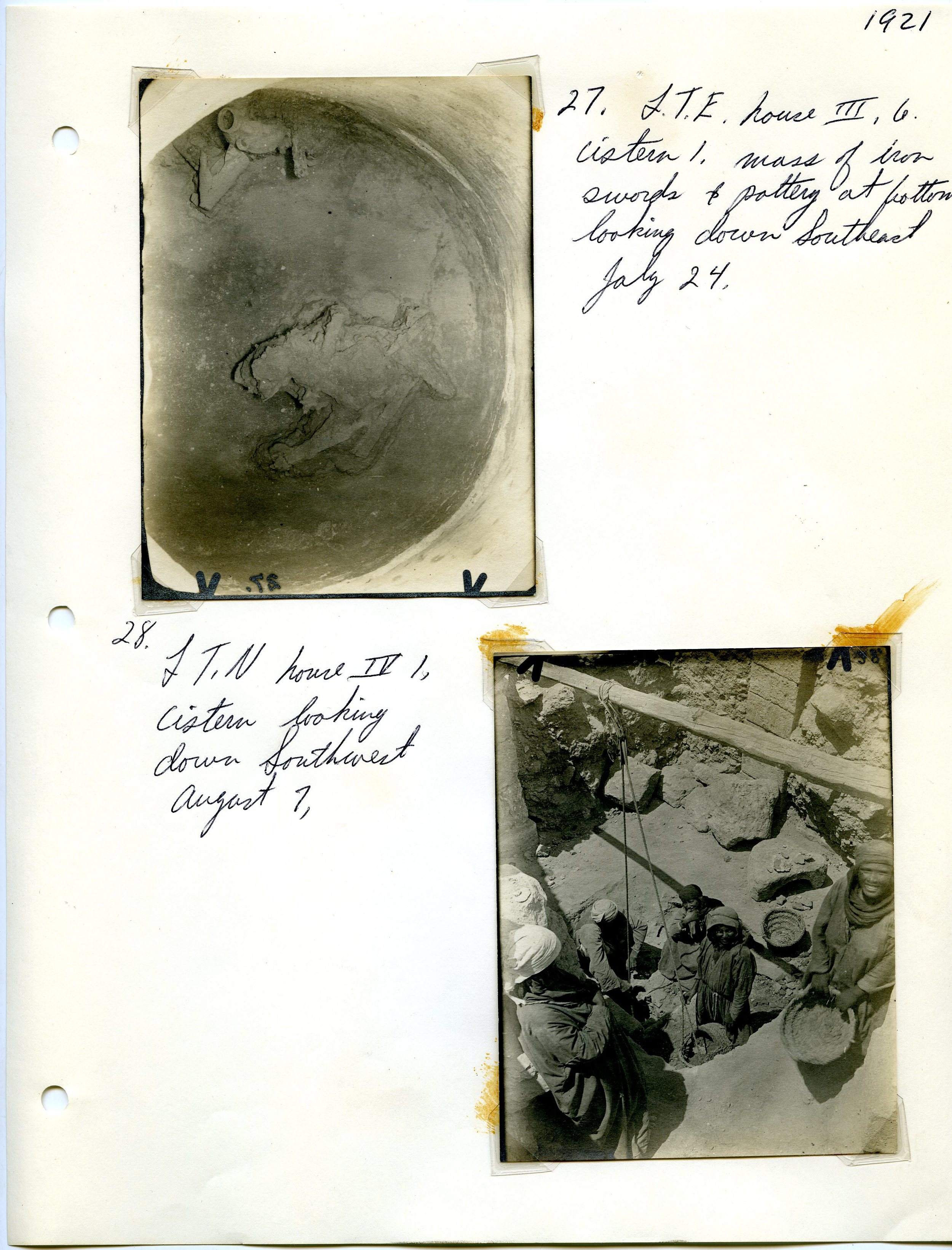

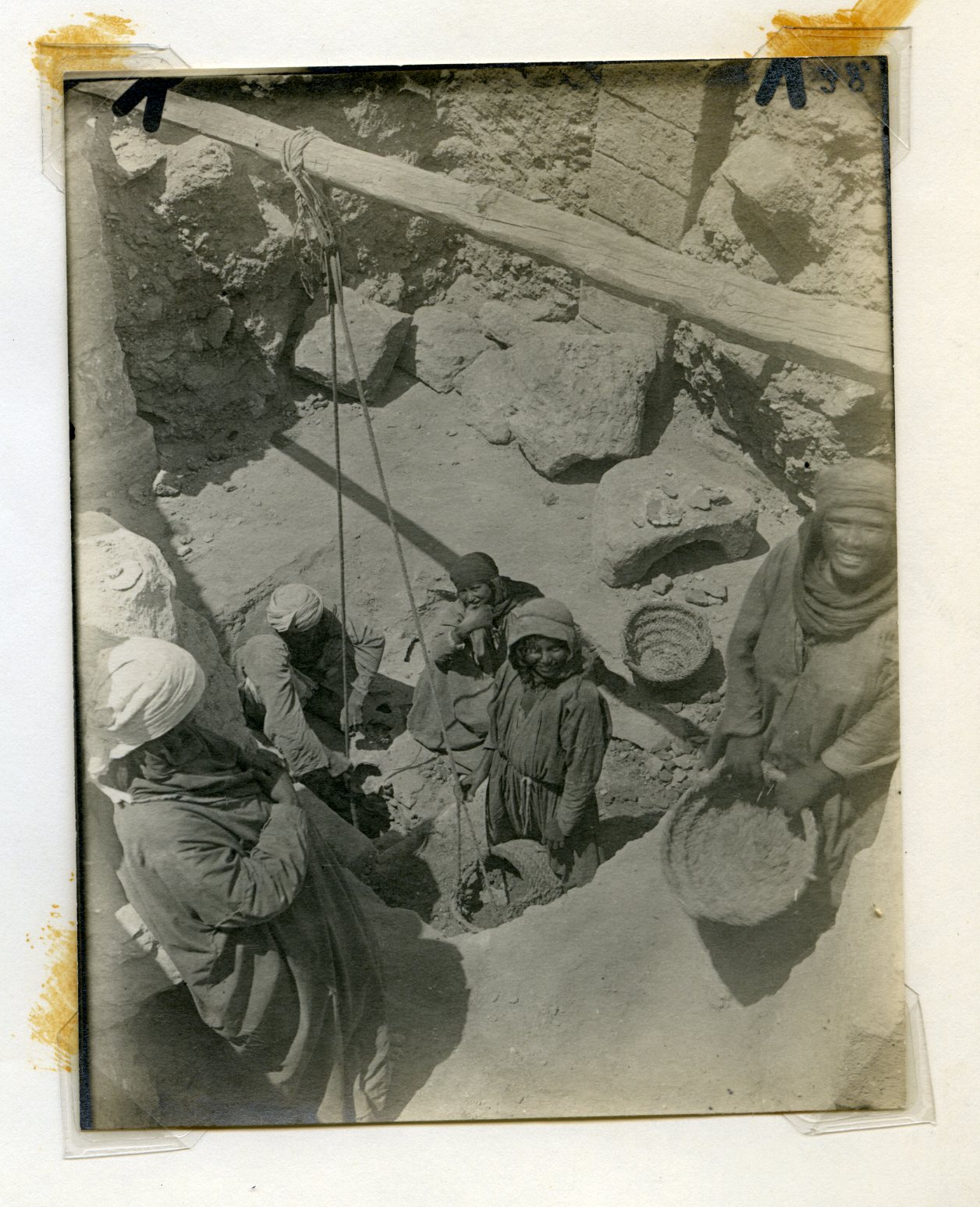

Unable to identify individual buildings, the historian must resort to other means to piece together domestic space. A number of theoretical options are available, such as discussions of the logic of space and the way in which people can be modelled to have moved through it. More specifically of interest for the archaeologist, several cisterns were uncovered in the process of excavation at Beth Shean, each of which contained a significant amount of material. Some cisterns produced predominantly pottery, and 3.1 in particular contained a number of more identifiable pieces, including part of a flask of St. Menas travelling with a pilgrim back to Beth Shean from the shrine of Menas near Alexandria.

Two inscriptions from the Tel monastery (Ovadiah) reinforce the view that the Byzantine buildings sharing the Tel were frequented by wealthy families (especially women) engaged in offerings to the local monasteries and churches. From the fourth century to the seventh, domestic space on the tell is characterized by elite occupants; a very different story in these early excavations to the lower city excavated by Hebrew University.